The Essence of Non-duality

A Gateway to Spiritual Harmony and Artistic Elevation

for Poets, Artists, and Philosophers

Last update: July 11, 2024

TABLE OF CONTENT

-

Preamble

-

Chapter 1 – Lessons from Duality ✅

-

Chapter 2 – A Brief History of Non-duality in the West ✅

2.1 – Foreword: What this brief history of Non-duality is not

2.2 – Truth, truths, and Non-duality

2.4 – Non-duality in Antiquity

2.5 – Non-duality in the Middle Ages

2.6 – Non-duality at the end of the Renaissance

2.7 – Non-duality in the age of Enlightenment

2.8 – Non-duality in the Industrial Revolution

2.9 – Summary, stagnation & causes of enstrangement from the public

-

Chapter 3 – Non-duality: Philosophical challenges in Africa & other animistic cultures of the world ✅

-

Chapter 4 – Non-duality in the East ⏰

[Soon]

-

Bibliography

To access this article's sources, click here

-

Glossary

[Soon]

This article is designed to serve as a reference study to our readers and submitters, whether poets, artists, academic philosophers, independent scholars, and the learned minds. Whenever our other resources mention “non-duality,” “Samkhya,” the evolution of mythology, philosophical, or religious thought, or the philosophy of Revue {R}évolution, we recommend consulting this page for further insights.

Purpose:

The purpose of The Essence of Non-duality: A Gateway to Spiritual Harmony and Artistic Elevation is to

- introduce non-duality in accessible language and

- demonstrate its positive impact on poetic and artistic practices across 5 chapters.

Audience

This text is designed for poets, artists, and philosophers willing to

- cultivate contemplation and intellectual growth

- refine their craft–the primary benefit this article targets.

Explanations, bibliography, and glossary

Because this article intends to educate, the readers will come across new notions. New is not complex. Only new. For the reader’s comfort and to facilitate the learning process, all essential notions and ideas will be explained in simple terms directly within the text, eliminating the need for external links, to help readers maintain attention and focus.

This article will be completed by a bibliography—a compilation of books and other references supporting the ongoing research—and a glossary, a list of concise definitions. Relevant links will be thoughtfully integrated into the bibliography section, and when necessary, words requiring clarification will be added to the glossary.

The bibliography and glossary sections will expand with each new chapter's publication but will not be necessary to understand the text. Quotes introducing or closing new chapters will be referenced in the Bibliography section.

While academics are acquainted with bibliographies, self-trained poets and artists may not be. The author is incorporating a bibliography and a glossary to educate poets and artists in the practices of research, source validation, and understanding the fundamentals of essay writing.

Note to thinkers

While presenting a brief history of world philosophy, this study also addresses the relevance and efficiency of philosophy as a universal legacy in the pursuit of wisdom. By doing so, it goes beyond the common divides between Eastern and Western philosophy, classical and modern, or analytic and continental perspectives. Academic philosophers and independent thinkers questioning the relevance and progress of philosophy will receive clarity on the lack of progress in philosophical research today, and the general indifference of the public towards philosophy.

Language

The language used is crafted for readability and clarity. Poets and artists, often self-trained (autodidacts), may vary in educational backgrounds. Therefore, clarity and simplicity are the most efficient ways to shed light on the importance of non-duality in the fine arts, but also in the art of thinking.

Each idea, introduced as a short paragraph or standalone sentence, is numbered.

This article capitalizes central ideas: Duality, Non-duality, Knowledge, Truth, Harmony, Poetry, Art, Thought (philosophy) as they are introduced. Except for Non-duality, such capitalization occurs only once per chapter.

Tips for reading comfort

Lengthy texts can cause eye strain. To alleviate this tension, feel free to utilize the zoom-in/zoom-out shortcuts on your laptop. These options are available in the top menu of your browser under "View," allowing you to adjust text size for optimal readability. Additionally, consider adjusting the light controls on your screen for optimal comfort. Reading with a dimly lighted screen is easier. Adopt a slow reading pace, pausing when you need it. A reading method and study guide is provided below (paragraph 12) to enhance your comfort and ensure you derive maximum benefits from this article.

INTRODUCTION

«Knowledge without conscience is but the ruin of the soul.»

–François Rabelais, Gargantua and Pantagruel, (16th century)

1. Understanding the role and importance of philosophy in the development of intelligence poses many challenges due to one factor–materialism. In recent history, the primary concentration of human intellectual energy on action and manufacturing, which the dominance of technology and commerce highlights since the Industrial Revolution, holds considerable implications.

2. Globalization and the information age have accelerated interconnectedness and established competition as a rule and measure of success. As a consequence, since the mid 20th century, education efforts in OECD countries ––an intergovernmental organization including Europe, Turkey, the Americas, and Oceania mostly, whose aim is to stimulate economic growth––focus on fast and gratifying ways to extract value from the physical world, thereby obliterating (wiping out) what leads to action: thought, the domain of philosophy. Within this framework, a deficit, a lack in intellectual capabilities impedes the cultivation of

philosophia, the pursuit of wisdom.

3. Aiming for wisdom conditions clarity in reasoning and decision-making, an essential skill to grapple existence, but also the foundation of any creative intent, and of science, which has, etymologically, less to do with numbers than the ability to organize and validate knowledge. Indeed, the term "science" originates from the Latin word

scientia, denoting knowledge, awareness, and understanding. Any endeavor devoid of

scientia

and its deeply nurturing quality to the mind, intellect, and spirit dooms the practice of wisdom to invisibility.

4. Yes, wisdom is a practice, an existential muscle, so to speak, that is trained by observation (study), experience, and encouraged by inner impulse or rather personality tendencies. Wisdom causes us to question the very nature of reality, to inquire existence beyond matter (what our 5 senses can fathom), find answers, that is, discern what is true from what is false, and realize what our finitude implies.

5. Human societies are inherently materialistic. Materialism isn't confined to politics or economics, or to the 21st century only; Materialism is existential. It shapes our perception of value solely from a material standpoint. Across ancient philosophical canons, from less religious texts like Stoic literature to more authoritative religious scriptures, there is a common theme warning against seeing life through the lens of matter only. So, materialism predates modern capitalism, which is a culmination or extreme manifestation of it.

6. Therefore, even amidst highly materialistic times, those who are naturally inclined to seek wisdom, which is spiritual in essence, meaning, detached from material pursuits, are present. This inclination towards wisdom may arise from inherent tendencies or be nurtured through exposure to canonical literature or oral traditions. In our current materialistic context, where the practice of wisdom has been pushed into the background, the value of wisdom, as well as the function of those who are natural wisdom seekers or passers, saints, poets, philosophers and scholars, disciples, and aspirants, is either ignored (rendered obsolete) or recuperated to fit dominant materialistic ideologies, as exemplified by the epidemic of social media poets, or the insidious infiltration of identity politics in the academia, another discreet effect of materialism.

7. While ancient wisdom and contemporary saints consistently caution against materialism, manifested in desire and avarice (greed), human societies do require political and economical organization as they depend on physical resources for their sustenance. In ancient religious and mystical traditions, these material aspects turn malevolent, or destructive, only in the absence of scientia, wisdom.

« What is matter if the Spirit leaves it? »

–Satguru Ram Lal Siyag, Yogi, modern Saint and Samarthguru - Public speech, 2006, Bikaner, Rajasthan, India

« Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink; or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothes? » –

The Bible (Matthew 6:25).

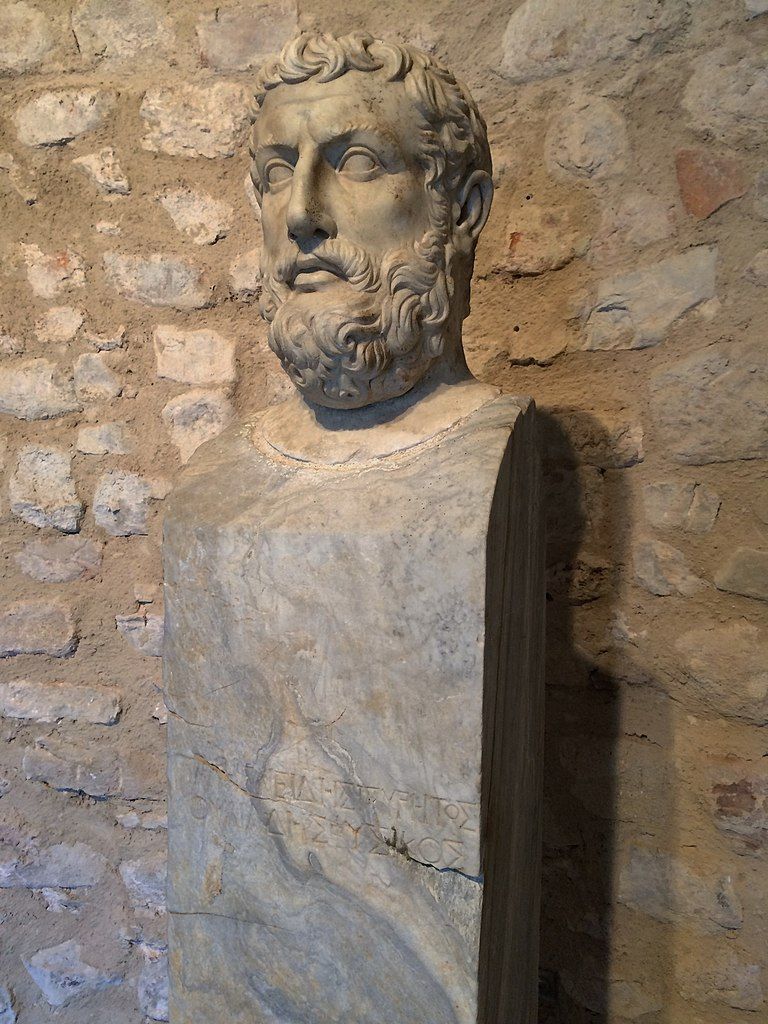

SCOPE OF THE PRESENT ARTICLE

8. We are currently witnessing a pronounced devotion to materialism, an unrestrained pursuit of desire satisfaction. The liberal arts, once cultural pillars that elevated education and society, now find themselves diluted in mass culture whose aim is to entertain, amuse, divert, rather than to cause to contemplate.

9. Materialism hinders wisdom, where thought, reason, and introspection flourish. Thought, a tool that can either serve materialism or wisdom, is rooted in philosophical competence—the ability to think correctly. This competence is crucial for cultivating a taste for wisdom, essential not only for addressing existence but also, within this article's scope, for expressing genius and sublimity in creative pursuits.

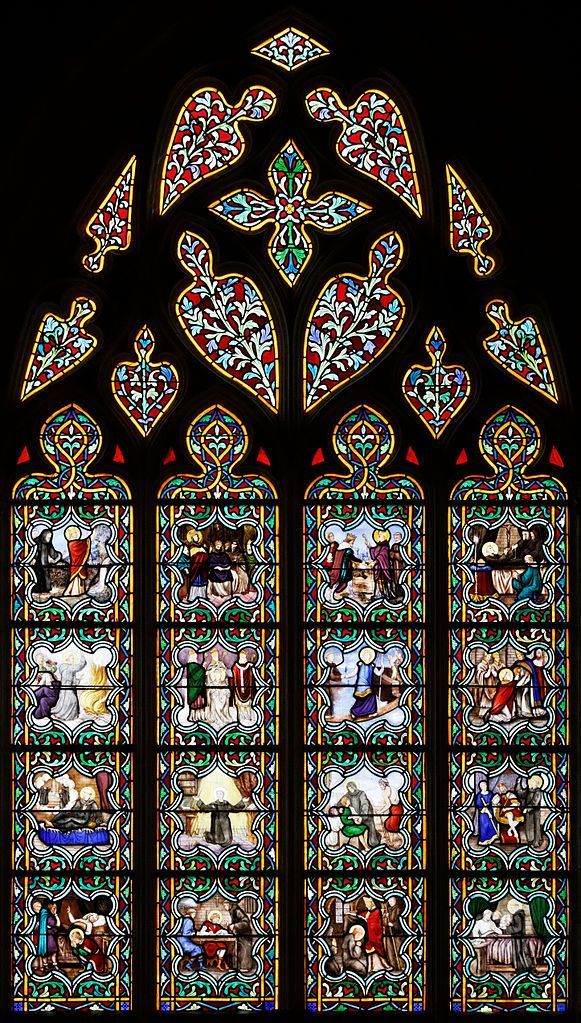

10. I won’t discuss the toll materialism exacts on our existence, here. That reflection may find its place in a separate article. As a mystic, I deplore the desolation of our inner lives—manifest not only in poetry and art, but also in the overall fabric of our existence. This is all the more disheartening since this intellectual and spiritual aridity is neither necessary nor inevitable.

11. Materialism is an effect of dualism, the perception that the inner and outer world are distinct entities, therefore separated. This article aims to illustrate how Non-duality, a philosophy prioritizing wisdom, reconciles these domains. Focusing on what’s absolute, complete, rather than relative and incomplete, non-duality not only solves existential paradoxes, but defragments knowledge.

HOW TO READ THIS ARTICLE & BENEFIT FROM IT

Reader and author engagement

12. This subject appears difficult and intimidating. It is not, as non-duality is harmony, the pursuit and privilege of poets and artists, and the first aspect of reality in Samkhya philosophy, as you will discover later on in this article. Harmony, as a force, is soothing for the intellect, and favors genius in existence and creative pursuits.

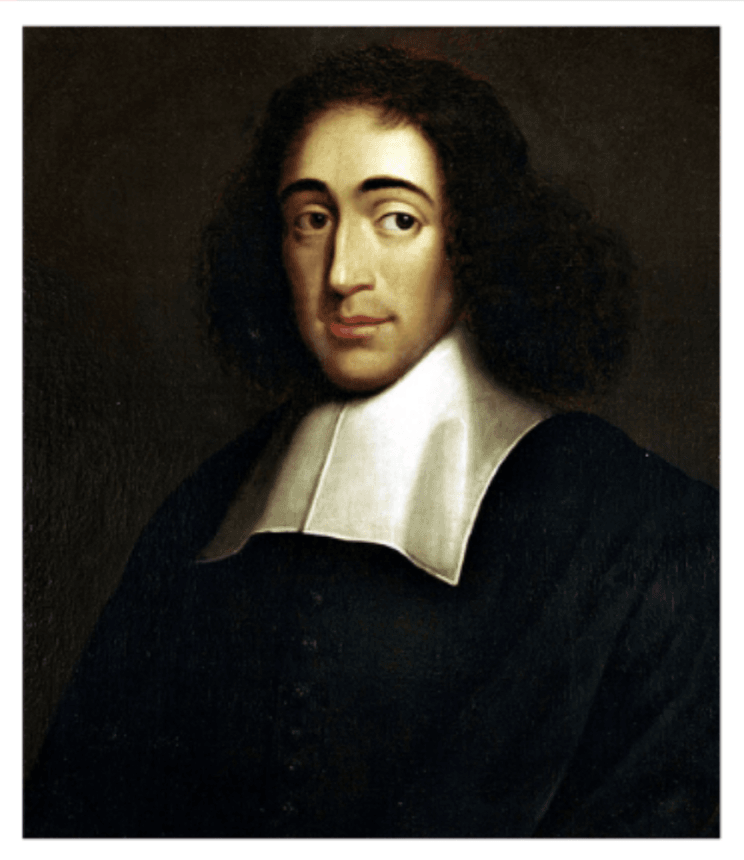

13. It is a dynamic movement of transformation, from the many to the one, we will engage in together. The only thing required from the reader/seeker is concentration, and a vivid will to see through this inquiry, and apply the method it contains to your creative practice.

How this article benefits poets, artists, and philosophers

14. This article aims to help you (i) grasp the nature, role, and connection of Culture and Religion, (ii) understand the responsibility bestowed upon poets by the gift of poetry, (iii) recognize its implications for artists and philosophers, and (iv) offer a practical method for creating poetry, art, and wisdom-oriented literature based on the principle of non-duality, which as we've already mentioned, favors a more complete comprehension, and as a consequence, enhanced creativity.

15. Our primary objective is to present these subjects in a clear and intelligible manner to provide practical benefits. To achieve this, we've crafted the text to maintain your attention, avoiding unnecessary jargon for fluidity. While the language is accessible, the content engages contemporary poets and artists in developing the philosophical competence expected from guardians of Culture, incorporating logic, historical references, literary composition, and philosophical reflection.

Reading and study method

16. For those engaging with "The Essence of Non-duality: A Gateway to Spiritual Harmony and Artistic Elevation," whether poets, artists, philosophers, or seekers, we suggest a deliberate, repetitive, and attentive reading process. Keep a notebook handy to jot down any salient points, ideas, questions, or thoughts that prompt further reflection.

17. We'll provide explanations of relevant concepts within the text, eliminating the need for external internet links that may distract you. Our goal is to illuminate your intellect, fostering openness, focus, dynamism, mobility, flexibility, and sharpness, avoiding confusion. Do not hesitate to contact the author for questions or clarifications. If you prefer reading aloud or find it beneficial, feel free to do so. We will add audible chapters to each page in the future.

18. Engaging in both reading and listening is a potent learning method, as this allows you to assimilate and integrate the subject of study by immersion through two primary senses, rather than relying on just one. I also recommend taking notes on a paper notepad to engage your sense of touch, a third sensory input that will mobilize and sharpen your intellectual faculties.

19. Should you require a dictionary for personal reasons, consult one at your convenience. In the near future, we will include a glossary with ongoing additions for reference. For vocabulary building and definitions, consider using reputable dictionaries in print or online, such as Merriam-Webster, Oxford Dictionary, Cambridge, Google Dictionary, etc. Wiktionary has become an interesting resource for definitions and etymology.

20. To counteract the distractions caused by technology and social media, mute your phone and place it in a different room. This may seem obvious but do not overlook the impact of technology and social media’s power of nuisance on your concentration and intellect.

- Set aside 30 minutes to 1 hour, or more if possible, to read and study The Essence of Non-duality. It's best to do this daily, but if that's not feasible, aim for weekly sessions. For instance, if you are a poet, an artist, or a seeker, you could designate Saturday morning or another convenient time to develop your intellectual and contemplative skills with The Essence of Non-duality. Thinkers who are trained intellectually, can focus on the evolution of non-duality beyond Western perspectives, especially if you're a philosopher in academia seeking insights into its global variations.

- Keep a paper notepad handy while reading, and use online notepads only after completing a chapter.

- We recommend reading each chapter multiple times for better retention and understanding.

- If you find yourself drawn to explore topics beyond what the author has provided, check out the article bibliography with recommended books, accessible via the link at the end of each chapter.

- Feel free to contact the author for questions, clarifications, or relevant observations through this

form.

21. A French translation of this text by the author will be available in the coming months.

PRAISES & SALUTATIONS

22. In the Yogic tradition, to which the author belongs, writers striving to unveil the Truth and enrich divine literature invoke and recognize divine inspiration with a preamble in any of their written endeavors. The author also extends gratitude to you, the audience, also divine in form, for your attention. With this foreword, the author pays homage to those recognized in the west as "muses," yet transcending them—verily the divine presence residing within us all. You can read this poem (and a light introduction to dedications in writing) here.

CHAPTER 1 - Lessons from Duality

«Mortals have settled in their

minds to speak of two forms,

one of which they should have

left out, and that is where

they go astray from the truth.»

Parmenides (535 BC) – Fragment of lost poem

1.1 – Reminder: The importance of etymology

23. Etymology is the study of the origins of words. The word "Etymology" stems from ancient Greek, etymon, which can be translated as "true meaning" and logos, "word," but also "reason, logic." It is a foundational discipline and a treasure trove of knowledge for writers and artists, whose role is to guard and build Culture. Etymology grounds poets and artists in the original meanings and essence of words, which remain unchanged, despite their diverse uses over time. Linguistics studies the evolution of words.

24. To understand the importance of etymology, think of your own sense of self. Unless afflicted by a psychiatric condition, you wake up each day with an innate awareness, a clear understanding of who you are, regardless of the diverse experiences that may come your way. Here’s an example. Every morning, I wake up as Murielle Mobengo, and that doesn't change no matter how my day went—whether it was filled with joy or challenges. I may dream of being Van Gogh or Baudelaire, but those artistic aspirations don't alter my fundamental identity as Murielle Mobengo.

25. Similarly, words have a core essence that stays constant, giving them the stability to be dynamic and versatile. Philosophers recognize this, often sticking to the original terms when discussing various philosophical concepts. For example, when exploring Nietzsche's ideas, they'll start with the German term "Übermensch" before translating it into English. Phenomenologists, a class of philosophers who observe events from the perspective of the self, will first mention "aletheia," an ancient Greek term for revealed truth, before providing an explanation. Likewise, in Eastern philosophical traditions, concepts are introduced in their original language before being explained in modern terms.

26. This article will follow this approach, introducing concepts in their original form before diving into their significance in English and tracing their evolution over time (and other modern languages when necessary). By understanding the original meanings across different languages, such as Sanskrit, ancient Hebrew, or Arabic, we aim to deepen your understanding efficiently.

27. We'll summarize these entries in a glossary for your convenience, though you won't always need to refer to it as the article provides explanations within the text. A link to the glossary and bibliography will be included at the end of each chapter when necessary. The glossary is for comfort and aid in memorization, offering occasional clarifications. Understanding, however, is essential, and will ensure efficient memorization and practical use of the concepts and method exposed in this article.

Having established the importance of etymology for dispensers of knowledge (poets, artists, and philosophers), let's focus on the etymology of non-duality. This ends subchapter 1.1 on the importance of studying etymology for dispensers of Knowledge.

BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENT

1.2 – Etymology & meaning of duality and non-duality

28. Non-duality is a compound, a term derived from combining two words to create a new concept. "Non" originates from Latin, has evolved into “no” in English, and denotes negation or the absence of something in its "non" state. For instance, "non-conformity" means the absence of conformity, conformity being the adherence to form, etymologically.

29. The term "duality" also has Latin roots, stemming from "dualitas," which describes the state of being double or dual. This suggests the existence of two separate components, yet opposing, or even antagonistic (conflicting, hostile towards each other).

30. For example, in metaphysics, a branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of reality, the duality of good and evil is a recurrent theme of inquiry, as well as existence and death, God and the soul, cause and effect, etc. These dichotomies (a dichotomy is a division between two things that are perceived as opposite) are central to many religions. Religions are metaphysical in nature. The interplay between duality and religion will be further examined in subsequent sections and chapters, such as "Western Monism & African Philosophies of Non-duality," "Is Non-Duality Eastern?" and "Non-duality & Religion."

31. "Duality" refers to the existence of two entities, and contrasts with "plurality," which involves more than two. The term "Dualitas" shares an etymological connection with "duel," a formal combat between two individuals involving deadly weapons, undertaken to settle a matter of honor. This connection traces back to the Latin word "duellum," from “duo” (two) and “bellum,” war. Note that in linguistics, "duality," "duel," and “dual” find their roots in the Latin word "duo," meaning "two."

32. From our recent exploration of the original, that is, authentic definition of the word "duality,"we now know that duality describes a situation in which two entities exist in opposition, which implies conflict or cancellation of one by the other. Therefore, duality isn't mere “bothness” or peaceful coexistence; it suggests strife, hostility, and inherent contradiction. As a consequence, non-duality is a state of oneness or unity, absence of separation, and absence of conflict. This will be further debated.

This ends subchapter 1.2: The etymology and meaning of duality and non-duality.

1.3 – The purpose of duality and how it affects knowledge

33. The human perception of life is dualistic. We separate good and evil, male and female, youth and maturity, black and white, color and absence of color, sound and silence, life and death, fullness and emptiness, poverty and wealth, illness and health, among others. Educational systems reinforce this dualistic perception, not to a fault. For example, separating sound and silence prevents confusion. Separating childhood and adulthood helps us manage our expectations, understanding that babies don't immediately speak or graduate to earn a living.

34. So what would be the purpose of non-duality in existence? How and why does it benefit us? As discussed earlier, duality is how our senses translate our physical experience and surroundings. Duality helps us organize physical knowledge, respond to immediate physical situations, and understand our surroundings.

35. In other words, duality allows us to navigate, to move through the physical world safely. Imagine you're jogging in a park and you encounter large stones or trees much heavier than you. Duality acts as your guide, helping you maneuver around these obstacles to avoid injury or harm while you run. Without this ability to distinguish between yourself and external objects, you might collide, run into these obstacles, unaware of their solidity or immovability. In essence, duality provides us with crucial sensory information about our surroundings, ensuring our physical safety.

36. Up to a certain limit, duality safeguards our physical being. That limit is death, which is inevitable.

37. Indeed, when it comes to deeper or more subtle aspects of reality that transcend physical senses, duality proves inadequate. These questions revolve around fundamental aspects of existence: identity, the purpose of life, overcoming personal obstacles, and grappling with existential fears.

38. Here are some examples that will resonate with all, questions that us, poets, artists, and philosophers contemplate in our lives and creative practices without always reaching a definitive answer:

Who am I?

What am I supposed to do?

What is my purpose in life?

What is the purpose of existence?

How can I get over a painful experience in life?

Why do I fear death?

How can I live a peaceful or joyful life?

What is happiness?

Is there a life after death?

How not to fear death?

What is consciousness?

What is love?

Does God exist?

39. Trying to answer these questions through a dualistic lens is bound to be ineffective and cause great distress on individuals. As it has been established in paragraphs 33-35, duality is designed to address physical problems, problems that our five senses can figure out, not metaphysical ones, that go beyond, or transcend the senses.

40. The natural conflict and opposition found within duality will confuse our understanding and hinder clear answers to these subtle and vital existential questions.

41. Modern Western philosophy, rooted in dualism, exemplifies this fact. It faces challenges in making headway (progress) in providing satisfying, universal, and authoritative answers to these questions.

42. As a result, modern philosophy struggles not only to spark renewed interest among the general public but also among poets and artists, who often have a closer connection to the public than academic philosophers. We will explain this further in the next chapter.

43. So, when addressed with a dualistic mindset, subtle existential inquiry often leads to paradoxes that the intellect (the repository of all knowledge gathered through the senses) cannot solve. This irresolvable internal contradiction or logical failure causes perpetual doubt, ineffective thinking, and is called an aporia.

44. For instance, the question of God's existence falls into this category, as God transcends physical perception and is often experienced through intuition or faith, which operates beyond the limitations of the senses. Since atheism is dualistic in essence and relies solely on the inability to prove the existence of God by the senses, atheists often draw the conclusion that God does not exist. This is not a criticism of atheism, rather an explanation of its mechanism.

45. When confronted with an aporia, the intellect tends to disregard the unsolvable issue. However, this doesn't resolve the problem; instead, it lingers within the intellect, persisting as ignorance, doubt or failure. The intellect is essentially a problem-solving tool, and when it is unable to function effectively, it becomes weakened. A weakened intellect is susceptible to fragmented knowledge and erroneous reasoning. It tends to be involved in, or, to see relative knowledge only, which leads to gradual ignorance.

46. In the general context of human lives, aporias cause immense existential distress. For knowledge dispensers such as poets, artists, or philosophers, these irresolvable paradoxes endanger their intelligence, jeopardize their success, expose them to increasing failure, and pose a threat to the integrity of Culture. Given these challenges, cultivating a non-dualistic mindset becomes particularly valuable.

47. Having established the definition, mechanics, and effects of duality within this sub-chapter, it is evident that:

- Duality involves two entities.

- Duality implies perceiving life through the lens of distinctiveness, separation.

- Duality implies polarization, that is, a conflicting, hostile relationship between these entities, leading to irresolvable paradoxes known as aporias.

- Aporias fragmentize knowledge, weaken intelligence, and predispose individuals to ignorance, which is particularly problematic for knowledge dispensers such as poets, artists, and philosophers, threatening the integrity of culture.

- Ignorance exposes knowledge dispensers to failure, as their role is to safeguard cultural integrity.

With this understanding of duality, its purpose, mechanisms, and its effects on knowledge, let's end Chapter 1 now, and shift our focus to the definition, nature, and historical significance (meaning) of non-duality across geographies, canons, and time periods.

END OF CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2 - A brief history of Non-Duality in the West

2.1 Foreword: What this brief history of Non-Duality is not

48. Given the apparent complexity of reality and the many questions it raises, various theories have emerged throughout human history to explain its nature. Typically, "reality" refers to the objective world outside ourselves, perceived as separate from us and experienced through our physical senses.

In Chapter 1, we’ve already established that:

- Duality separates and is conflicting in nature (etymology)

- Duality deals with physical problems

- Duality is ineffective in solving existential or metaphysical problems and leads to unsolvable paradoxes, aporias

- Duality fragments knowledge and therefore, fosters gradual ignorance

- Duality threatens the integrity of Culture (it favors ignorance)

- Duality exposes knowledge conveyors like poets, artists, and philosophers, to failure (also a consequence of the latter).

49. Since we've already addressed the nature of duality, this section doesn't indulge in aimless exploration of duality vs non-duality, or traditional academic debates regarding the equal validity or value of non-duality and duality. Non-duality is the absence of duality, and therefore the absence of the attributes and consequences of duality mentioned above. Duality and Non-duality are not equally valid. They are certainly not of the same value because they yield very different outcomes.

50. This tendency to see things as equally valid contributes to the stagnation of Western philosophy and its disengagement from the public, as it fosters confusion and conflict disguised as complexity. We embrace the French proverb: "What is well conceived is clearly expressed, and the words to express it come easily." Unfortunately, non-duality is not well conceived in academia today, and this confusion permeates all cultural life. Philosophers are responsible for the ideas that circulate in the city. When they are confused, the public is confused.

Now that we've clarified what this brief history of non-duality is not, and established that non-duality is the absence of separation, the absence of conflicts and confusion, and the absence of irresolvable paradoxes that weaken intelligence, foster ignorance, and threaten the integrity of Culture, let's shift our focus to the essence of non-duality, beginning with Truth. This ends subchapter 2.1. Remain alert and pay attention to the next subchapter on Truth and truths.

2.2 Truth, truths, and Non-duality

51. The focus of this article is non-duality. By focusing on non-duality, we aim for

- Harmony instead of conflict

- Clarity instead of confusion

- Simplicity instead of complexity.

52. This approach aligns with the ancient Greek concept of aletheia, where Truth naturally contains clarity and as a consequence, discloses what’s hidden, illuminates the intellect, which in turn, leads to empowered action or non-action. Harmony, clarity, and simplicity are all attributes of Truth, which is one, that is, non-dual.

53. Some may argue that there are multiple truths, a perspective with which many individuals sympathize. For those who hold such a perspective, the belief in "one's own truth" persists, often in contrast to a universal Truth that they deny or perceive as separate from other truths. How should we regard this viewpoint?

54. Firstly, we’ve established that separation is duality. “Separate truths” imply duality, which leads to fragmentation, polarization, conflict, confusion, and gradual ignorance.

55. Second, if such opinions were valid, truth would become relative to an extreme, that is unstable and chaotic. Truth is stable and meaningful, that is, harmonizing in nature. It helps make sense by providing reliable knowledge. Chaos is disorder, the inability to produce and organize reliable information: ignorance. So, such perspectives on the relativity of Truth are devoid from Knowledge.

56. Truth, by its very nature, is absolute, whole, and complete—not relative. Its absolute quality provides stability, essential for effective thinking, problem-solving, inquiry, introspection, and life in general.

57. All life processes, from the simplest to the most intricate, thrive on stability. You are able to read this article because your attention remains stable. You can walk, run, or drive from point A to point B because the ground beneath you is stable. A variety of musical instruments can produce identical harmonious sounds because the laws of music are stable.

58. Similarly, when your body is stable, not jittery, you can perform tasks like drinking coffee, answering the phone, or planning your groceries while maintaining focus. Stability enables you to return to this article while enjoying something sweet.

59. Just as stability facilitates various aspects of life, it also plays a crucial role in seeking Truth. While it may require effort, stability ensures that Truth can be found. This idea resonates with the mystical concept found in many religious traditions, such as Yogic and Judeo-Christian canons, that what constantly changes is not true and that God is (found in) stillness. This underscores the importance of stability in discerning Truth.

60. Therefore, pursuing universal Truth is a highly desirable goal for knowledge dispensers and humanity as a whole.

Now that we’ve cleared doubts and confusion emerging from the opinion that there are many truths, and established what ties non-duality, truth, and stability together, let's dive understand what ties Non-duality to the Divine. This ends sub-chapter 2.2 on Truth.

2.3 Non-duality & God

61. In the upcoming sections, you will meet philosophers who have contributed to the history of non-duality in the West. You'll observe that these thinkers often connect concepts such as Being, existence, convergence, or harmony—fundamental to non-duality—with the Divine, for a simple reason.

62. Beingness, oneness, convergence, and harmony represent absolute qualities, suggesting completeness and permanence beyond mundane human comprehension. To articulate what exceeds human senses, people often use terms like "God" or "gods." Why? The origin of the word "God" or "divine" sheds light on this.

63. Although the exact origin of "God" remains uncertain, it is believed to stem from an archaic Germanic language, which traces its roots back to the broader Indo-European language family—the source of many languages spoken in the Northern hemisphere.

64. Linguists suggest that “God" may have evolved from an Indo-European word associated with invocation, sacrifice or libation (the pouring of liquid in worship) and is also more likely linked to "Gautam" or "Gotam," likely a compound derived from Sanskrit, where the sound go / gau / gu connotes bright, light, clarity, and "tamas" denotes "obscurity," implying the dispelling of ignorance, one of the definitions of the word “guru.” We will get back to tamas and guru later.

65. As for the word "divine," it originates from Latin roots associated with daylight, sun, and the revelation of knowledge, but also Sanskrit roots (devi, deva). Over time, human reasoning has thus linked the word “God” with:

- Harmony, the capacity to discern meaning beyond sensory opposites.

- A form of knowledge deemed worthy of sacrifice and reverence.

66. These qualities, transcending human senses, are inherently absolute and unifying in nature.

67. Indeed, the reason why humans often invoke terms like "God" or "gods" to symbolize what lies beyond human perception is rooted in language itself. Language serves as the structure through which meaning is expressed and understood. So, from the perspective of language, terms such as God, absolute, divine, harmony, oneness, and wholeness are synonymous, as throughout the history of human language, they have all been pointing to, or expressed the same underlying reality or meaning.

68. What organized religions have transformed "God" into, diverging from Its original, universal, i.e, non-dualistic meaning, is a separate matter not discussed in this article. The focus here is on language and meaning—an area that poets, artists, and philosophers, by definition, seek to and must master.

69. This article does not wander into matters of belief or disbelief either, nor does it address personal preferences regarding the existence or nonexistence of God. Its intention is to remain factual, as language is grounded in logic and fact.

This ends subchapter 2.3. Now, let's dive into a brief history of non-duality in Western and African philosophies. The reader is asked to remain alert while we establish how philosophies of non-duality have been expressed and have survived, maintaining a unified clarity through time and geographical diversity.

Bust of Parmenides. Source: Wikimedia Commons. License Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0. Photography by Sergio Spolti

2.4 Non-duality in Ancient Greece

70. The reader is invited to closely examine the development and nuances of monism in Western thought, tracing its evolution from its simplest to its most elaborate forms, starting with Ancient Greece, the cradle of Western civilization. The most notable form of non-duality in Ancient Greece is the doctrine or philosophy of monism.

- Non-Duality as "Monism"

- Time: 6th-5th century BCE. BCE stands for "Before Common Era." CE stands for common era, from year 1 onwards. A standard convention in chronology is that time decreases before our common era, also described as “BC,” Before Christ.

- Era: Antiquity

- Geography: Ancient Greece

- Key Thinker: Parmenides

- Movement: The Eleatic School

- Geography: Ancient Greece

71. In a philosophical poem, which has been partially preserved through fragments collected by Plato, Parmenides engages in discourse with a female deity who imparts knowledge about Being. Parmenides later established the Eleatic School to propagate Monism, or the doctrine of the One. He observed that beingness is inherent in (common to) all things, animate and inanimate alike, leading him to the conclusion that only Being is real and truly exists; everything else is mere appearance or illusion.

72. Before Parmenides and Socrates (5th-4th century BC: 470–399 BC), many thinkers began to question mythology and inquire the nature of life, the cosmos, and existence, often adopting dualistic or pluralistic perspectives. Parmenides stands apart in his assertion that, whether the universe appears purely elemental (physical) or divine, one fundamental characteristic unites everything within it: beingness. The term "Monism" is derived from the ancient Greek word "monos," meaning "one."

This ends subchapter 2.4. , Non-duality in Antiquity. Let's see how Oneness evolved during the Middle Ages.

2.5 Non-duality in the Middle Ages

73. After the fall of the Roman empire, Christianity took center stage in Europe. As a new religion, Christianity needed to establish its authority against former religious systems inherited from Eastern and ancient Greek, therefore authoritative philosophies.

- Non-duality as the purpose of dialogue

- Time: (5th century - 15th) 476 - 1492 CE

- Era: Middle Ages

- Geography: Europe

- Key Thinker: Anselm of Canterbury

- Movement: Scholastic Philosophy

- Key events: Fall of the Roman Empire (476) • Fall of the Byzantine Empire (1453) • Invention of the printing press (1444 - Gutenberg) • Discovery of the Americas (1492)

74. One standout thinker was Anselm of Canterbury, an Italian philosopher and theologian. He believed in the idea of God being both everywhere (immanent) and beyond physical things (transcendent). He argued that we can think about God, that is, oneness, and from that, we can understand that God exists. In Western philosophy, this method is called an ontological argument, a thought process that progresses from the idea of God to the reality of God.

75. As for this form of inquisitive dialogue, conducted with self or another to explore abstract (non-physical or above the physical) phenomenon such as God, Time, Existence, etc., it is termed as a "dialectic."

76. These elements of style are given to poets and aspirant poets for further exploration. We will discuss them in the last chapter of this study, where you will be introduced to a method of writing that aims at expressing non-duality. Artists should also pay attention, especially if they are aspirant writers. Artists who are not aspirant writers are asked to focus on ways to apply these elements of style, and Non-duality itself, to their creative processes. The author will shed more light on this in the Method Chapter. Poets, aspirant poets, and artists who seek to express Beauty and Truth in their work, and participate in the emergence of a renewed and elevated Culture should study The Essence of Non-duality.

77. Creatives with a vision or engaged in interdisciplinary projects or seeking to express novelty should study The Essence of Non-Duality. Thinkers of lofty thoughts and philosophers who wish to break free from the academic habit of uncertainty, hyperbolic doubt, hyper-specialization to a level that rigidifies the intellect, obscure verbosity, intellectual dependence, and the inability to bridge the gap between theory and practice (which are all connected and make philosophy unappealing and seemingly useless to their students and the general public) should study The Essence of Non-Duality. Feel free to reach out to the author for questions (contact form in paragraph 20).

This ends Non-duality in The Middle Ages, subchapter 2.5. Our focus now shifts to the next historical era in Western history, The Renaissance.

Stained-glass window ("vitrail") representing 16 phases of the life of Saint Anselme in in the cathedral of Quimper (Brittany, France). Licence:Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0. Photography: Thesupermat

Portrait of Baruch Benedictus de Spinoza (1632-1677). Public domain. Source: Wikimedia commons.

2.6 Non-duality at the end of the Renaissance

78. More than two millennia later (that is 21 centuries later, exactly), Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza posited that God and nature are one and the same, and that everything that exists is a manifestation of this single substance.

- Non-duality & Ethics

- Time: 17th century

- Era: European Renaissance: The beginning of the Renaissance overlaps with the Middle-Ages: Italian Pre-Cento (14th century) • Quattrocento (15th century) and finally, Cinquecento, a late Renaissance extending to the 16th/17th century and reaches all Europe.

- Geography: The Netherlands

- Key thinker: Spinoza

- Movement: Spinozism

- Key events: Multiple. The Renaissance itself is considered a key event in history.

79. Here, a quote from Spinoza's Ethics to illustrate this form of renewed monism: "By ‘God’ I understand: a thing that is absolutely infinite, i.e. a substance consisting of an infinity of attributes, each of which expresses an eternal and infinite essence. I say ‘absolutely infinite’ in contrast to ‘infinite in its own kind’. If something is infinite only in its own kind, there can be attributes that it doesn’t have; but if something is absolutely infinite its essence ·or nature· contains every positive way in which a thing can exist—·which means that it has all possible attributes."–– Spinoza, Part 1, Ethics, 1677

This ends subchapter 2.6 on Non-duality at the End of the Renaissance. Let's move on to the Enlightenment era, when rationalism dominated.

2.7 Non-duality in the Age of Enlightenment

80. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a prominent figure in philosophy, contributed to the development of non-duality in the West. He proposed that reality consists of indivisible mental elements called "monads." These monads perceive the universe from unique perspectives that are inherently harmonious. In essence, harmony underlies diversity, serving as the condition for every phenomenon's existence. Leibniz attributed the orchestration of these monads to the Divine.

Non-duality & Reason

- Time: 18th century

- Era: The Age of Enlightenment / The Age of Reason

- Geography: Germany

- Key thinker: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

- Movement: Non-duality as Monadology

- Key event: American War of Independence (1761 - 1791) & French Revolution (1789 - 1799)

81. Leibniz discovered something new on monism. He elucidated the relationship between cause and effect, their interconnectedness, and the overarching importance of causation. Leibniz states that "the monads have no windows through which something can enter or depart. Nothing can influence them from the outside. There is no way they can come into interaction with each other, except through God."

This ends subchapter 2.7 on Non-duality in the Age of Enlightenment. After the Enlightenment epoch, western societies expanded thanks to industrial innovation. Let's examine how Non-duality survived the Industrial Revolution. The reader is asked to remain attentive to what follows.

A diagram of I Ching hexagrams owned by Leibniz (1701). The author's intention is not to mystify you, but to demonstrate an important aspect of the 18th century: the ongoing dialogue and intellectual exchange between East and West regarding the essence of reality and the concepts of harmony and change. Leibniz likely added annotations, now faint due to the passage of time, which include numbers familiar to us and historically recognized as the Arabic system of notation. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Public domain

Portrait entitledThe Philosopher Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel

by German painter and restorer Jakob Schlesinger (Berlin, 1831) Source: Wikimedia Commons. Public domain. Hegel's philosophy is influenced by Christian mysticism and extremely poetic. This is perhaps due to his friendship with poets at the time, one of them being Friedrich Hölderlin, a poet worthy of your attention, dear reader.

2.8 Non-duality during the Industrial Revolution

82. German philosopher Friedrich Hegel portrayed non-duality as the fundamental unity of reality, where opposing elements gradually merge and acknowledge a common focal point: self-awareness. He termed this process a dialectic, which is essentially a form of dialogue—the art of discussion which involves two parties using common language and meaning systems.

- Non-duality as “Dialectic”

- Time: 19th century

- Era: Industrial Revolution

- Geography: Germany

- Key thinker: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

- Movement: Absolute Idealism

- Key event: Industrial Revolution

83. In Hegel's framework, dialectic unfolds through the interplay of thesis (a statement), antithesis (its opposite), and synthesis (union, convergence). This progression towards unity reflects the natural flow of human history. It begins with the assertion of a thesis or idea, followed by its development or assertion of power. This is then met with an antithesis or opposing viewpoint, leading to conflict, rejection, or struggle. Finally, synthesis occurs, bringing together the opposing perspectives into a unified whole.

This ends subchapter 2.8 on Non-duality during the Industrial Revolution, the most recent era before our hypermodern age. Let's observe the evolution, the dialectic, of Non-duality throughout the ages. Please remain alert.

2.9 Summary, contemporary stagnation in academic philosophy & causes of enstrangement from the public

84. To summarize, in Western thought, the concept of non-duality has evolved over time as follows:

- In Antiquity, Non-duality was expressed as a sense of shared beingness.

- During the Middle Ages, non-duality found expression through the ontological argument, which sought to establish the existence of God based on reason.

- In the Enlightenment period, non-duality became absoluteness or permanence, encompassing what is relative or changing. As a consequence, diversity was seen as expressing absolute harmony rather than chaos.

- In the beginning of modern times, particularly through the philosophy of Hegel, non-duality emerges as the outcome of a dynamic process, from opposition to self-consciousness or self-recognition.

85. Many theories concerning non-duality have emerged since the 19th century, all drawing upon or commenting on these four authoritative works. Despite ongoing exploration, there has been little notable progress beyond these authoritative texts. Today, the main three schools of non-duality in the Western context are:

- Materialistic Monism is known as physicalism or materialism. This form of monism asserts that the fundamental substance of reality is physical matter. According to materialistic monism, everything, including thoughts, consciousness, and emotions, can be explained in terms of physical processes. Since monism implies absolute stability (permanence, infinity), materialistic monism is a seriously flawed theory as matter is relative, unstable, and impermanent (finite).

- Idealistic Monism: Idealistic monism holds that the fundamental substance of reality is mental or spiritual in nature. This viewpoint suggests that the physical world is an extension or manifestation of a deeper, mental or spiritual reality.

- Neutral Monism: Neutral monism proposes that neither physical matter nor mental substance is fundamental, but rather there exists a neutral substance or principle from which both the physical and mental aspects of reality emerge.

As you can see, except for physicalism, which should be excluded from non-dualistic philosophies, the last two remaining schools tend to gravitate around the foundational works of Parmenides, Spinoza, Leibniz, and Hegel. Since the question of Beingness and Wisdom is central to philosophy, not making progress here means a stagnation of philosophy as a whole in the West, and obviously, from stagnation, all kinds of confusion and endless debates lacking practicality.

86. Practicality is the core of philosophy. Thought is useful inasmuch as it serves action and informs and harmonizes our individual and collective lives. When philosophy ceases to be practical and focuses on abstraction and theories that have no direct proof in life, it is bound to stagnate, degenerate, and it is only logical and consequential that the people in the city lose interest in it.

87. The father of philosophy in the West, Socrates, has been described by his disciple Plato as an active, practical force within the city. Engaging with poets, artists, thinkers of all schools, politicians, youth, and the common man. Questioning them so they can experiment with ideas actively in their lives and find answers, with active knowledge and wisdom applicable to existence individually and universally, not endless abstract quests.

88. Plato depicted Socrates, regarded as the father of Western philosophy, as a force within the city. His constant interactions with the citizens, questioning poets, artists, thinkers from various schools of thought, politicians, youth, and ordinary citizens aimed at liberating their intelligence from opinion. He practiced a method called "maieutics," the art of bringing forth meaning. The purpose of this approach was to reveal enlivening ideas, wisdom that was applicable to both individual and universal contexts, rather than getting lost in endless abstract debates. Socrates even died like that, as he left us a live description of his own death and its effects on consciousness that resembles a moving piece of poetry in the Katha Upanishad, a canon of Hindu poetic philosophy describing the extinction of all senses as the soul leaves the body and unites with Brahman, the universal consciousness or God.

89. From an etymological perspective, philosophy indeed means “love of wisdom.” Neither love nor wisdom is abstract. Love is practical, so is Wisdom. Love and wisdom are matters that concern everyone, not just professional thinkers. When philosophers, from the East, West, South or North, neglect to cultivate and share this love for wisdom with their fellow citizens, chaos prevails in society.

This concludes Chapter 2 on Non-Duality in the West. The reader is asked to maintain focus as we discover how Non-duality has been expressed in Africa.

END OF CHAPTER 2

« By ‘God’ I understand: a thing that is absolutely infinite, i.e. a substance consisting of an infinity of attributes, each of which expresses an eternal and infinite essence. I say ‘absolutely infinite’ in contrast to ‘infinite in its own kind’.

If something is infinite only in its own kind, there can be attributes that it doesn’t have; but if something is absolutely infinite its essence or nature contains every positive way in which a thing can exist—which means that it has all possible attributes. »–– Spinoza, Part 1, Ethics, 1677

« The truth is the whole. It is not an abstract whole, but is filled with differences [...] The absolute whole, however, is spirit. »

–Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (19th century)

CHAPTER 3 - Non-duality: Philosophical challenges in Africa & other animistic cultures of the world

3.1 Historical challenges

90. Identifying philosophies of non-duality from Africa presents challenges due to several main factors:

- Limited historical records: The documented history of the humanities in Africa is relatively recent, making it difficult to trace the development of philosophical traditions.

- Diverse cultural structure: The African continent consists in distinctive cultural regions, the product of unique religious history and political events:

- Muslim-majority countries: Found in North-Western Africa (Maghreb) and the Mashriq (which includes Egypt and Sudan).

- Christian-majority countries: Predominantly located in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Further divisions: Within these religious divisions, there are additional subdivisions based on factors such as former invasions (Arabic influences in the Maghreb and Mashriq) and former colonial territories (e.g., French/Belgian, German, English, Portuguese, and Dutch influences).

91. When mentioning “Africa,” we usually think about Sub-saharan regions, where descendants of Bantu people, who are dark-skinned, reside, a rather archaic and simplistic categorization, considering the interconnectedness of African peoples. For example, a 2017 joint study of the Max Planck Institute in Germany and the University of Tübingen concludes that modern Egyptians share common ancestry with sub-saharan peoples. Also, the Bantu expansion may have significantly influenced the cultures of Eastern and Southern Africa. Head to our Non-duality bibliography for references and further resources on this subject.

92. Bantu cultures, along with those in the northern portion of Western Africa (Mali, Senegal and countries along the West coast, from the river Gambia to the Gulf of Guinea) share oral traditions. In traditional African societies, griots, oral poets and bards, are responsible for transmitting cultural knowledge through individual and collective initiation processes. However, unless supported by a robust initiation system, oral traditions tend to hinder transmission of knowledge. Additionally, due to the fragmented nature of Africa's history, territory, and its diverse cultural landscape, identifying common philosophical traits is challenging.

93. This section is concerned with the existence or non-existence of a non-dualistic philosophy in the culture of the Mandé peoples (Francophone & Anglophone Western Africa) and peoples of Bantu origins (the rest of Africa), particularly in Sub-Saharan regions, emphasizing rites and traditions that hint at the existence of non-dualistic philosophies in the past.

94. Non-dualistic philosophies in the Maghreb and Mashriq countries, mostly based on Islam, will be explored in Chapter 4: Non-dualistic philosophies of the East.

3.2 The philosophical challenges of tribal cultures

95. For reasons we will expose here briefly, certain peoples known as “tribal” in nature did not develop elaborate philosophical systems similar to the Eastern or Western ones. Elaborate here means: encompassing all layers of human perception, from legend to reason to religion. If you want to go deeper and find out why, consider enrolling in our Evolutive Mythology class.

96. The denomination “tribal,” “first tribes” or “first nations” has been used for various historical, political, and economical purposes and propaganda. Early Western anthropologists in the 60s/70s like Émile Durkheim or Marcel Mauss have used those terms in an attempt to describe a group of tightly-knit people sharing blood ties, language, land and culture, and organized in a clan, with a chief-like figure ruling over the group’s life.

97. Many of these African, Oceanian, American, and Asian indigenous tribes may now be relatively Westernized and modernized, with some retaining tribal structures or codes underneath westernization. Let's illustrate this with historical elements from modern-day Central and southern Africa to understand this phenomenon.

- Illustration to understanding tribal structures in today's world

98. The Republic of Congo, home to more than fifty tribes, is organized in a political north-south division with 3 linguistic groups speaking a variety of languages stemming from Bantu, Pygmean, and Ubangian-Sudanic roots. Ethnic groups from the north are usually better educated, closer to power centers, and wealthier than southern ethnic groups. The most educated and wealthiest individuals from the south are usually closer to those of northern descent or married to members of northern tribes. Settling in or interacting with the Congolese within or without their land without understanding these social dynamics means missing an essential, formative aspect of the society. Here’s another example: the Rwandan genocide against the Tutsi in the 90s, a civil war motivated by ethnic identity politics and tribal resentment.

99. Ethnic structures tend to persist in traditional societies which rely heavily on ancestry lore, folklore and mythology as vessels to guard the history of their peoples. Traditional societies of the world are animistic in nature. Animism is a form of religion where transcendence, the absolute or the Divine is nature exclusively, the land, the elements or animals, which must be propitiated to benefit humans, their families and ancestors.

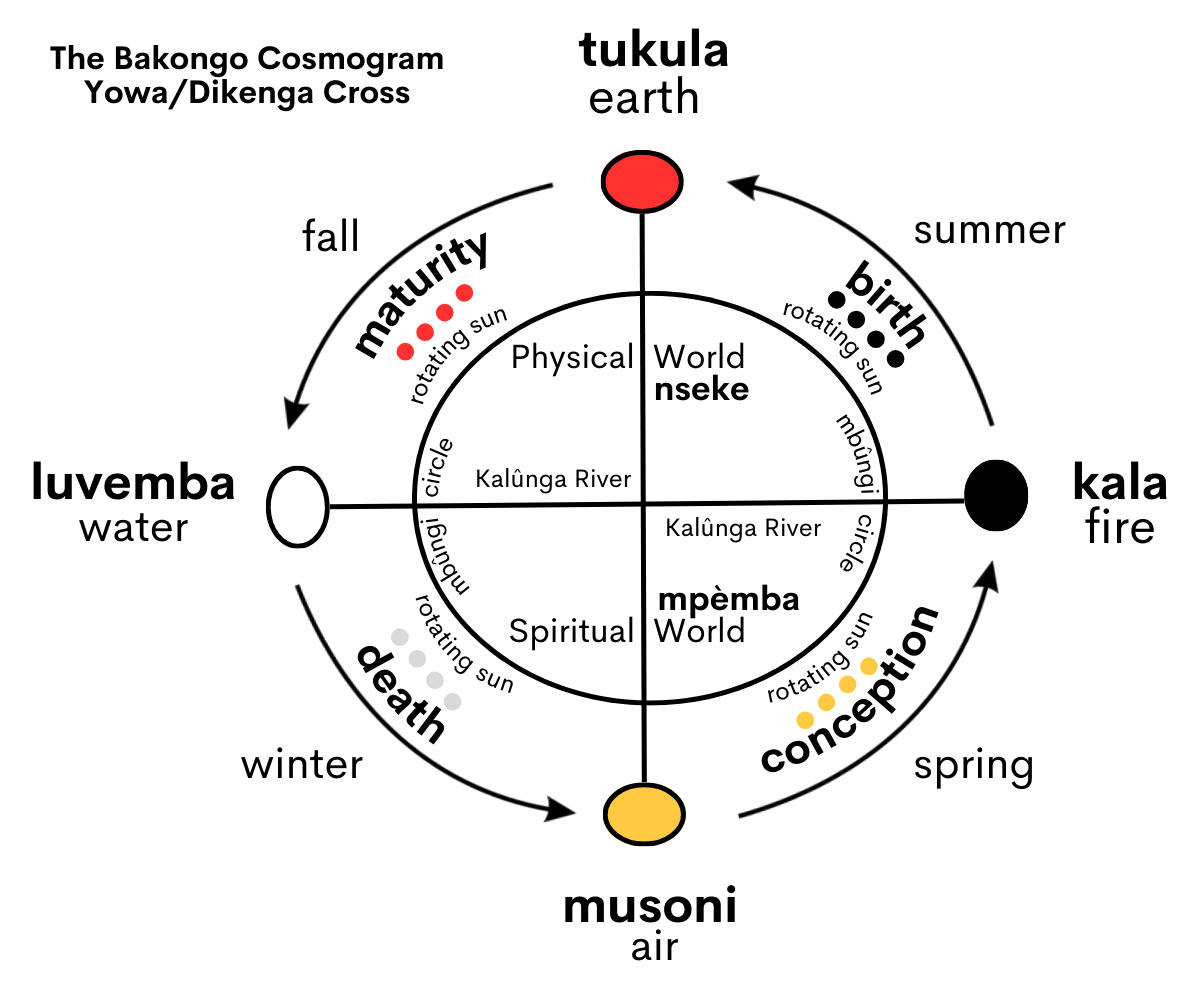

Source: Wikipedia / Wikimedia commons. Author of the cosmogram: unknown. The language in the Bakongo Cosmogram is "Kikongo," or Kongo language, a Bantu language spoken in various parts of Central Africa.

Left: The Bakongo Cosmogram (Congo / Central Africa) represents the cycles of life in a monad-like schema. While circles in symbolic schemas and mandalas tend to represent oneness and suggest non-duality, the Bakongo Cosmogram is animistic in nature, not because it is strictly elemental but because the experiencer of nature is absent from it.

In ancient cosmogonies from Greece to India, nature is made up of five elements. The fifth element is usually ether, also called skies, heavens or space. Ether is the transcendental aspect present in nature, a divine element connecting nature to the individualized consciousness: the observer/experiencer, the divine self, a portal to the Divine.

When the ether element is absent from the inception of a philosophy, it tends to be animistic, that is, extremely dualistic and local, relying on legend, lore, ancestor worship and mythology solely, like witchcraft and sorceries (voodoos, etc), for example, which are widespread in north and southern Africa.

This may explain why these philosophies did not evolve into fully-fledged religions. Organized religions develop theologies, philosophical discourses on the Divine, and esotericism. Esotericism defines millenary spiritual lineages where masters initiate seekers of Truth (disciples) into divine knowledge.

Gurus, messiahs, saints, disciples or apostles constitute the pillars of esoteric traditions. This form of organization makes them universal, that is, relevant to people beyond their place of birth or culture. Mainstream religions illustrate this fact, to some extent. Though born in the East, monotheistic religions have been adopted by all.

Among the initiatic traditions prevalent on Earth, Yoga stands out drastically. It expands beyond cultures, nations, and ethnicities with non-violence (a philosophy called "ahimsa" in Sanskrit), contrary to most monotheistic or polytheistic religions and philosophies, which have resorted to violence over the ages to convert people.

In addition to African cosmogonies, Zoroastrianism, First Nations of America, and Sumerian cosmogonies are also based on a 4-element philosophy. To understand the relationship between philosophy and the five elements, read Plato or enroll in our Evolutive mythology course. Link in bibliography.

3.3 Universalism: How progressive philosophies are born

100. The development of an elaborate and progressive philosophical system requires transcending land and ethnicities to aim for universal knowledge—discoveries that are applicable to the entirety of the human species, not just certain categories within it. This is why animistic societies do not typically develop enduring philosophical legacies. If they do, these philosophies often become obsolete as they fail to resonate beyond their specific tribes or ethnicities. The inability to develop a comprehensive philosophical system hampers knowledge growth and affects scientific, artistic, literary, and spiritual development.

101. It is unfortunate that humans often reject universalism, whether in tribal societies or, surprisingly, in modern westernized countries preoccupied with identity politics. The universal impulse has been driving the progress of our species from times immemorial. These are indeed challenging and dangerous times for humanity.

102. In conclusion, it is difficult to find non-dualistic philosophies in purely animistic societies. The beauty of Non-duality is that it encompasses all levels of human perception, recognizing animism as one step in our evolution. Animism may be transcended if its practitioners make conscious efforts to question its relevance to their lives. This is also valid for any dualistic philosophy / perception.

This ends chapter 3, Non-Duality and philosophical challenges in Africa & other animistic cultures of the world. Next chapter will introduce you to the expression of Non-duality in the East. The reader is asked to pay attention to the various expressions of non-duality in Middle and Far Eastern cultures, throughout the ages.