BRAIN STUFF | Genius is rare

But not only. Once divorced from its original transcendental essence—the Divine, the Creator, Nature, the Bestower of all gifts—genius, unfortunately, reveals itself as a manifestation of ignorance and hubris (tamas). These qualities, chaotic and destructive in nature, undermine all intelligence.

Archeology of Genius

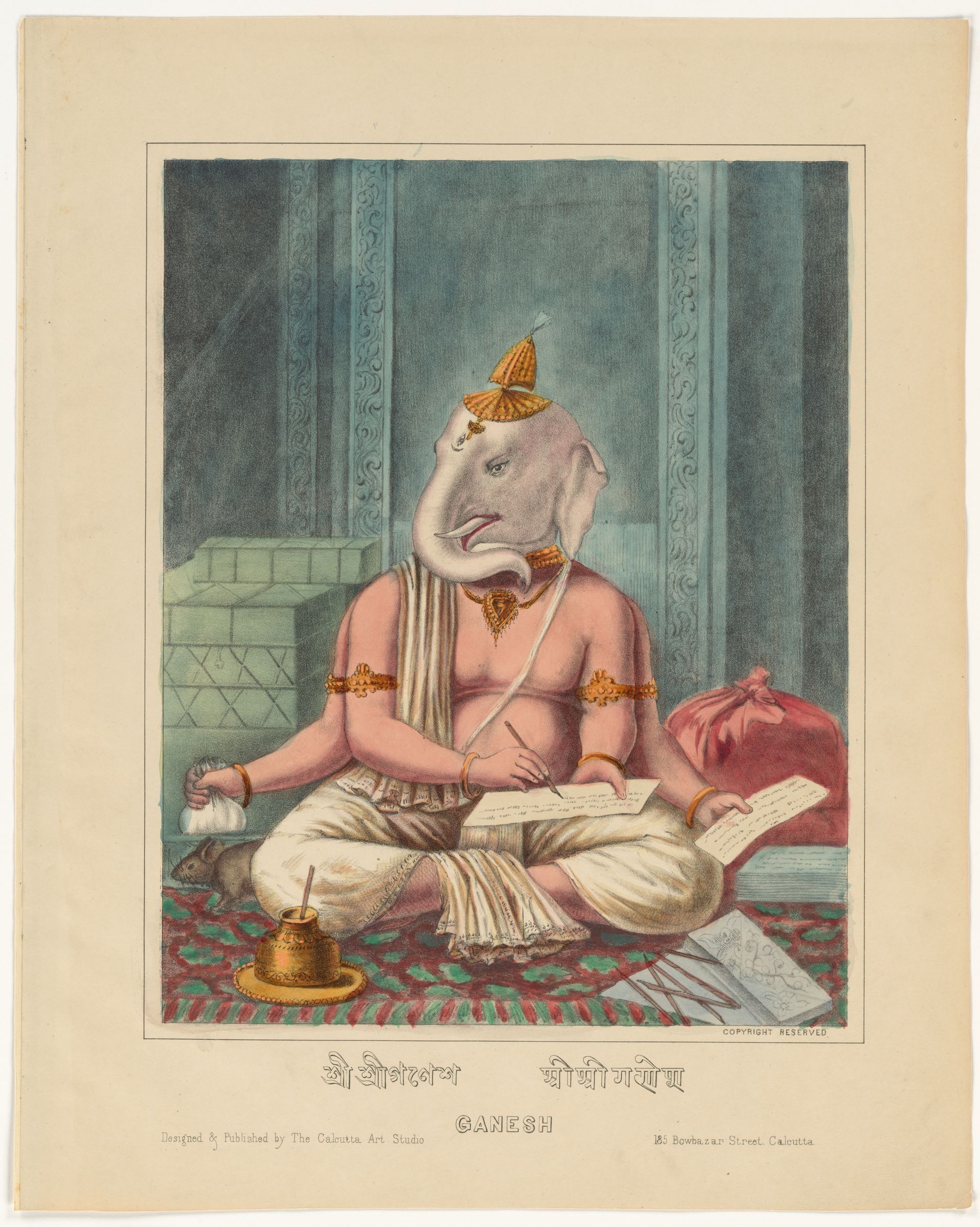

According to world mythologies, a genius is a supernatural guide and protector within each individual, the symbol of their spiritual essence and guardian of destiny. While the etymology of the term remains somewhat ambiguous, there may be a connection to the Arabic term "jinn," prevalent in Islamic mythology to describe supernatural beings with both positive and negative attributes. The term also finds its roots in the Latin "gignere," to beget, produce, and generate. The French equivalent for people has retained this original sense, “les gens”, those who have been generated.

In Roman mythology, the genius was considered a spirit safeguarding the destiny of a family or clan, akin to what African animism identifies as a "familiar"—a personal spirit devoted to serving a specific individual, and a subtle, inner source of inspiration in ancient Greece, with Homer and Socrates’ famous

daimon. Throughout antiquity, genius was perceived as both divine, having positive qualities, and demonic, having negative qualities.

The Renaissance, Da Vinci, and Wealth

The perception of genius shifted during the Renaissance. Merchant states in Italy, such as the Republic of Florence or Venice, operated under an oligarchic system. These financial oligarchies, small groups of wealthy people having control of a country or organization, provided relative political freedom, supported certain intellectuals and artists according to their preferences, and dictated cultural fashion likewise.

For instance, the extensive list of influential patrons, ranging from the school of Andrea del Verrocchio to the Borgias, Sforzas, and Medicis, to the pope, and even to King of France François I, who supported Da Vinci, born into wealth with access to funding and networks from the outset through his father, serves as concrete evidence of this phenomenon.

In art, and to some extent, in certain intellectual domains other than science (where peer review mechanisms aren't present to ensure and validate performance), our contemporary era may have inherited this oligarchic and individualistic perception of genius from the Renaissance, where creative individuals tailored their work to suit the tastes and interests of the wealthy and influential. One of Revue {R}évolution's editorial team members refers to this phenomenon as "l'art officiel" in French, denoting art that is considered official or sanctioned.

As you can see, the contemporary concept of "genius" has deviated from its original foundation in the natural or supernatural manifestation of exceptional talent, lucidity, or extraordinary creativity. Instead, it is now often rooted in nepotism and entrism, where certain individuals establish dominance over others solely due to their access to financial wealth and influential networks.

In today's world, the idea of artistic genius has drifted significantly from the remarkable accomplishments of figures like Da Vinci because of the hegemony of technology (a domain the affluent control) which has diminished the artist’s curiosity and ingenuity.

Excellence is not Genius

Excellence should not be confused with genius; instead, it is a natural outcome. What many perceive as genius in Da Vinci's artistic achievements is, in reality, the product of excellence, rigorous training and craftsmanship. While under the guidance of Master Andrea del Verrocchio, a versatile artist skilled in painting, sculpture, metalwork, and forging, Da Vinci underwent thorough training in fundamental artistic and artisanal techniques. As his apprentice, he learned to grind pigments, prepare coatings, cut metals, and sculpt clay. Da Vinci probably had natural drawing skills, a prerequisite that few modern artists claiming genius or comparing themselves to Renaissance polymaths can truly claim.

However beautiful and mysterious the sfumato may be, it is a painting technique that Da Vinci likely learned or discovered in the process of his work. There is nothing genius in doing one’s job well, and excelling at it. It is simply expected. You expect your dentist or cardiologist to be excellent at what he does, not just average.

That said, there is genius in establishing the foundations of an ideal city with a hydraulic system capable of preventing pandemics, diverting the bed of a river (to ensure military advantage), creating new musical instruments, laying the foundations of modern urban cartography and human anatomy (Leonardo left 250+ dissection sketches of impressive accuracy for the time, according to modern physicians) early in the 15th century, etc.

Da Vinci's intellect was not confined to art and engineering; it embraced literature, with poets like Boccaccio, Dante, and Petrarch capturing his attention. His curiosity also led him to

The Natural History of Pliny the Elder, revealing the historical and scientific breadth of his interests. Only fate can produce an individual like that, and perhaps, a certain awareness of, and connection with his own inner genii. Who can control fate? Despite all our hypermodern technology and information, we are unable to control our individual future. We can't predict what will happen in the next minute either. As a species, we struggle to manage, or even respond to common environmental challenges that impact us collectively—unlike Da Vinci, a single man, who responded to the plague pandemic in Milan (1485) with a visionary plan for the ideal city. This level of selflessness and intellectual vibrancy is humbling. So, let’s be honest. There is no genius at this time, no polymath either, and this

Western obsession with Da Vinci is a strange matter.

The Master-Disciple Relationship in Knowledge Discovery (and Genius)

Knowledge requires a proper channel of transmission, and throughout history, this conduit has been peer validation. At Revue {R}évolution, poets and artists submitting their work are required to answer a question about their master in poetry and art. In my five years of serving as an Editor, I've observed a trend: we frequently receive exquisite or interesting pieces from individuals who openly acknowledge their lineage in their craft. These poets and artists attribute their calling to a revered master from the past, whom they admire and seek to emulate. They do not take offense at this question; rather, embrace it.

Furthermore, philosophers submitting to Revue {R} respond graciously to this question and express happiness and honor in acknowledging their philosophical lineage. One of them we highly recommend that you read is

David Capps.

Beyond Curiosity and Talk

Genius transcends mere curiosity and talk; it materializes in performance, tangible results, exceptional luck, and life-affirming endeavors—a legacy of knowledge that outlasts individual lifetimes. How many of us can honestly affirm that our work will be remembered six centuries later?

The majority of contemporary poetry appears to be forgettable within minutes. Poetic prowess and access to major publishing opportunities is now measured in social media following. If you've ever found yourself contemplating the lifespan of a tweet or the fleeting glory of a TikTok video, you'll know I'm not exaggerating, here.

As you now know, the same dynamics does not quite apply to artists, though. While they actively seek followers on social media (why, oh why?), their exposure often hinges on who patrons them. Quite the head-scratcher. This talk by scientist

Albert-László Barabási will either brighten or cloud your day, if this article hasn’t yet, or if you believe success in art is about talent and following your bliss and other common stupidities that may only cause your inner genii, a powerhouse of supreme intelligence, to want to ignore you.

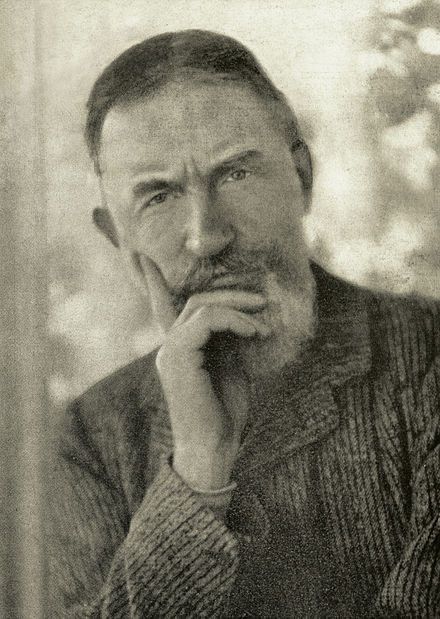

«I now want to give the common man weapons against the intellectual man. I love the common people. I want to arm them against the lawyer, the doctor, the priest, the literary man, the professor, the artist, and the politician, who, once in authority, is the most dangerous, disastrous, and tyrannical of all the fools, rascals, and impostors. I want a democratic power strong enough to force the intellectual oligarchy to use its genius for the general good or else perish.»

-- George Bernard Shaw, Major Barbara (1905)

Art & Plutocracy: An Old Story

In the broader context of human history, the ascendance of the financial industry has consistently promoted individual freedoms, a positive development. However, it has also resulted in the unfortunate consequence of certain individuals exercising superiority over the common man, as exemplified in this quote by George Bernard Shaw. His romantic affirmation and use of "the common man" to flatter our ordinariness already implies two biases: first, the prevailing notion that the common man requires saving, is a victim, and is inherently harmless and second, the idea that the common man may be idiotic. Let's agree to disagree, although our era may prove Shaw unfortunately right.

If Shaw were right, our society would be playing a game of two teams: Team Masses (poor and, let's say, not winning any trivia contests) and Team Wealthy. Not being in one would mean being in the other—no exception. I get the yearning for an upgrade; nobody wants to be the village idiot. So here you are, author of a visual or readable masterpiece trying to make it in a plutocracy, following billionaires on social media, hoping they'll accidentally hit the heart button on your latest post between yacht selfies.

Pause for a minute and think. In a world neatly split between the idiots and the wealthy, how does all that wealth get made? What noble causes does/can/will it serve? Is it just me, or does it sound a smidge delusional to think there's room for intelligence, exceptional smarts, excellence or genius in such a context? Am I laying down some harsh truth, or just dealing with reality?

In Plato's Republic, Socrates expressed that democracy is not the ideal political regime, only the lesser deviant. For it to function properly, the common man must strive for wisdom rather than succumbing to base desires, the pursuit of epithymia, a life centered on the gratification of sexual appetites, indulgence in food, and entertainment. Socrates' worst-case scenario became real, as humanity binge-watches and scrolls down on food selfies, self-selfies and God-knows what to evade Reality, where intelligence dwells and thrives. There is no space for polymathy or genius in such a context. When intelligence itself is in peril, polymathy simply becomes unrealistic.

So, ever since the European Renaissance, “Genius” came to describe exceptional talent or intelligence and the supernatural being was obliterated in lieu of the human individual, whose ego is corruptible and likes titles of domination. The word “polymath” had to follow the same sad trajectory.

Resources & books on Antiquity, Da Vinci & The Renaissance used in this article

- Léonard. Tout l'œuvre peint et graphique, Frank Zöllner 🇫🇷, TASCHEN

Taschen, the renowned German publisher celebrated for crafting exquisite and budget-friendly art books, has delivered yet another stunning edition. Their mastery in creating beautiful publications on art shines through in this captivating release. The book weighs 16 lbs (7 kgs), measures 11.4 x 15.6 in., and contains 712 pages of exquisite print quality with close-ups. A must-have for artists!

Also available

in English

Eye-opening and visionary, this timeless masterpiece, written in the 4th century BC, is a series of discourses between Socrates, his disciples and opponents. Every artist and poet should

study this to understand (1) the purpose and field of application of poetry and art in the City (2) the patronage and recognition dynamics in their environment. If you haven't

study Plato, you don't know what you're doing. Read slowly.

- Saga Science CNRS, Dans les carnets de Léonard, 500 ans après 🇫🇷

"In Leonardo's notebooks, 500 years later." A CNRS initiative. The CNRS is the French National Centre for Scientific Research.

Slightly deeper :

Genius Take 2: On Van Gogh, Nash, Ramanujan & Vedanta

Revue {R}évolution