POÎÉSIS | A Short Autobibliography

POIESIS

Memento Mori: A Short Autobibliography

"And when people heard his words, it was not only the sun, the play of fish, or the whispering of the willow that they depicted. It seemed that heaven and earth chimed together for one moment in perfect harmony, and the listeners would think with pleasure or pain about something that they loved or hated --the boy about his games, the young man about his lover, and the old man about death."

Hermann Hesse, The Poet

Douglas Adams novel The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy tells the fantastic story of a computer named Deep Thought. The thinking machine is programmed to discover the answer to the ultimate purpose of Life, the Universe, and Everything. After millions and millions of years, Deep Thought comes out with the solution "42." I turned 42 this year, and my whole life is making sense.

My parents left Congo-Brazzaville, a former French African colony, in the 70s and traveled to Madagascar, Senegal, Ukraine, America, Cuba and chose to settle in mainland France. I suspect my mother, a lover of wine, influenced my father's choice when they left Paris for Bordeaux, where I was born.

Bordeaux is nestled in the Bay of Biscay, in the ancient Gascony where The Three Musketeers fought Milady de Winter and Cardinal de Richelieu's never-ending plots. Bordeaux is my hometown. Yes, I am a native Gascon of Congolese descent. How exotic and romantic is that? Sounds a bit like science-fiction doesn't it? Well, stories gave me life. Not only stories of Gascon knights, but tales of a mischievous novelist, rhymes of cursed and dandy poets, and many philosophers' stories about our being-in-the-world--most of them German--have brought creative chaos in my life.

I am eleven again. It is late, I won't sleep because the thought of Chloe's imminent death saddens me. Chloe is a delicate, sweet, young woman in Boris Vian's novel Foam of the Daze. Her blitheness is coming to an end because a water lily appears in her lungs and begins to grow. I am sad and obsessed with it. I wonder how on Earth something so improbable and so dangerous can be so beautiful. "Beauty is always bizarre" once sang the dandiest of all dandies, Charles Baudelaire in Curiosités Esthétiques (Aesthetic Curiosities). My first poetical experience had happened; my poetry journey had begun.

I stayed busy being a kid for a while, then adolescence dawned on me. I didn't know what it was. I was changing, discordant, while infused with power. Or desire and shame. Or all of it. An awkward existential posture you think will last forever but which, fortunately, passes. I fell in love with boys who did not fall in love with me, and I scorned those who did because the real love of my life was Arthur Rimbaud. I hated that he was dead (and gay). How could anyone not fall in love with his impertinence, his responsibility for debauchery, his intellectual radiance, his immortality?

I kept falling in love with dead poets because they could never change. I kept falling in love with them also because I adored the tragedy in their lives. Misfortune shaped their souls into nameless colors and their tongues into constant melodies. People think lovers of poetry love poetry for the sake of poetry, but they don't. They love the longing of the human soul desperate to find her way back to a paradise lost. They adore her mourning, her song of joy and laughter within existential adversity. They love the sound of it, her intoxicating harmony.

Being intoxicated with the music other souls produce--that is 19th- and early 20th-century poets often intoxicated with absinthe--made me marry a man I had to divorce. I had no choice. I did not want to wind up absorbed with unpoetic things, with house renovations, barbecues, and invoices. I did not want to die like Madame Bovary's Emma, Flaubert's heroine trapped in a cage of reverie society and marriage built for her.

I made up my mind one day and decided to go away. I was 28 and I thought: What if after I go, my whole house falls? Not only my real house, the one I bought with no soon-to-be-ex-husband in the Paris area, but also my sanity, my metaphorical house. Like the one in Edgar Allan Poe's story "The Fall of The House of Usher" (Charles translated into French, by the way). Or the many houses which collapsed when Jean-Baptiste Grenouille left them in Patrick Süskind's deadly fragrant novel Perfume .

Reading poetry and falling in love with dead poets and novelists made a sissy of me. I needed strength. So I would open a bottle of wine. No, it wasn't a Bordeaux because I was in my Burgundy phase thanks to some Burgundy-Italian friends with whom I used to hang around. Burgundy, Italy, and Nietzsche. A criminal association. If you ever see a bottle of Chassagne, Italians and Thus Spoke Zarathustra in the same place, run. Italians will be charming, as usual. They will sing "Andiamo! Avanti! Or usher a ''Dammi un bacio, dolce Nera!" in your ears or quote Dante's Inferno , killing every last bit of the reasoning ability persisting in you. "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here."

Friedrich Nietzsche. A philosopher with a poet's soul. The beginning of my intellectual and spiritual quest. A mind and a heart ignited. A dead soulmate, again. I had to accept his absence, because beyond death, Nietzsche gave me a treasure which would never cease to grow. He told me who I was and why I was hiding. He helped me look at the weak and the meek within me, thinking she is glorious being weak because Christ said so, people told her.

Having Albert Camus explain to me why human life is an absurdity of repetition ending with death in The Myth of Sisyphus and The Rebel made me understand the human condition. Having Camus show me how men and a child are courageous when facing The Plague helped me love the human condition.

Nietzsche, on the contrary, made me loathe life. Nietzsche will be Nietzsche, and he goes to the root of every human action and unveils its moral violence. He is the one who said "God is dead," meaning Goodness is mortal and human beings have found out. He is the one who prophesied the reign of what is mediocre, not remarkable, usual, fitting, dull, inert, correct: social. Friedrich foresaw that the Number will always rule. Hence, he showed the beauty of individual power, an aberration of human will, a force one must exert over many to be real. Otherwise, the human soul lives a mediocre life while the body dies a mediocre death.

Friedrich made me alert to Truth and Kindness in disguise. Yes, he was mad, half schizophrenic or paranoid or bipolar or all of it. As someone in my creative writing class beautifully said, these are "the extremes of life."

There is more.

Heidegger, a controversial German thinker, helped me understand what digital technology is doing to my biological and poetical body, this ability to own the narrative of my identity, something so sacred, so intimate before. This unquestioned, natural right which is now under constant scrutiny and extimacy, a word coined by the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan to describe the habit of making intimacy public.

Speaking of which, isn't it what the writing experience is all about? Is it possible to be an impersonal poet, an aloof artist living an impersonal life, and still touch the human, sympathetic chord in all of us? Can one experience while one remains neutral? This reminds me of a twisted poem by ee cummings, Anyone lived in a pretty how town :

one day anyone died I guess

(and no one stooped to kiss his face)

busy folk buried them side by side

little by little and was by was

As impersonal as these destructured sentences may sound, emotion remains, a mixture of loneliness and shared intimacy too--an oxymoronic experience only Poetry (and real life) can give. Here, anyone's body is ours, and we can visualize no one kissing it.

Poetry without the body is impossible or maybe it is possible, but it is no longer poetry, rather philosophy. I suspect I might be using philosophy to temper the ardors of the body. The body is a traitor. Left to itself, the body of an artist cannot be trusted. Think about it for a minute. Consider the long list of all artists who became crazed with love or hatred.

There is a French singer all French people my age used to love. Handsome, an angel face with a masculine charisma, a political activist, a poet. His name is Bertrand Cantat, and he is a Gascon too. Everyone remembers this Verlainian verse from him which sounds like an ode to the sea's immensity and existence's vacuity:

Aux sombres héros de l'Amer

Qui ont su traverser les océans du vide

À la mémoire de nos frères

Dont les sanglots

Si longs faisaient couler l'acide

Always lost

in the sea.

To the somber heroes of Bitterness

who could cross oceans of emptiness

To the memory of our brothers

whose song so long and languorous

flowed out the acid

Always lost

in the sea.

A beauty. Well, Bertrand Cantat killed his paramour (and his wife hanged herself when he got out of prison). Arthur Rimbaud shot his lover Paul Verlaine. He didn't kill him but Arthur ended in Ethiopia, selling guns, up until the end of his life. Louis Althusser, another genius philosopher, strangled his wife in a temporary crisis of dementia.

All these beings, sickly, tortured, deranged assassins, had genius, a heart on fire and great violence within them. Their light and darkness, added to mine, keep forming a puzzle. They ask a question I try to answer. The question of what it is to be human, to believe the stories our brains fabricate for us, fuel them with our emotions and build a life out of them. To be strong or fragile, so predictable because of them. To believe we are disposable flesh, mortal and unable to transcend it.

Charles Baudelaire, the subversive soul who authored The Flowers of Evil (Les Fleurs du Mal), will remain my last dead poet-lover. He didn't kill anybody or loathe anything except ignorance and bad taste. Charles said: "I have more memories than if I'd lived a thousand years."

The verse rhymes like me and tells what I have been hiding all these years. What turning 42 gives me the luxury to be, at last--a woman, now grown, liberated from the dictate of wild hormones and constant pleasing, armed with a pen (a laptop, actually), sharpened thoughts, and wild memories. I won't tell how I experienced excruciating pain and solitude when I was 10. I won't tell how I left Brazzaville ablaze with civil war when I was 18 or how I became a happy-worried mother, twice.

Neither will I tell how I found solace in the Bible, a literary masterpiece of promiscuity (too many people, too much sex, too much violence, wine, and a Divine surprise). Nor will I tell how I dated a Serbian spy when I was 33 and Joseph Conrad's book The Secret Agent helped me realize I was dating a slightly disturbed doppelganger of Brad Pitt. Or how I met a Canadian atheist mathematician (a mouthful) in the warmest Flanders night, married him (oops), followed him to Montreal, discovered the discrete poetry of the québécismes (French from Quebec) and Emile Nelligan, and Gilles Vigneault, and arrived in New York, and became a New Yorker. I still try to convince him that Poetry and some of his beloved complex equations form the answer to the mystery of life. I will tell him that being the exact opposite of me, Ghislain inspires me.

Enough with men and excessive emotions, I am going back to me and ending this long soliloquy. Blaise Pascal said : "the I is detestable." It'll be over in a minute or in a few years: I didn't tell you about Wendell Berry's poetic ability to bring tenderness to life like magic, or Noam Chomsky, who made me quit my job, or Michel Foucault, or Cesare Pavese, whose diary, The Business of Living, made me laugh when there was nothing to laugh about.

Wait, I didn't tell you about Henri Laborit, a neurologist obsessed with our elusive feelings in Éloge de la Fuite which means "praising the escape" (not available in English yet). I didn't tell you about Thom Yorke, Pink Floyd, The Verve, Serge Reggiani's vibrato which liquefies the soul or Jacques Brel and Stromae--two vibrant cynical poets we stole from the Belgians. I didn't tell you about poets who can sing with a microphone in a room packed with frenetic people. I didn't tell you about Mantra, the source of Music and Poetry and Life. I almost forgot to tell you about the poetics of African drums.

Maybe the I is detestable because her time is short. Enough name-dropping, a delightful European sport. It is good to be an old soul in a semi-young body, traversed by people from books and people from real life. Real people, book people: I have loved you and scorned you and lived a passionate life, as I was searching for the perfect existential rhyming. I have loved some of you again in a sort of "amicable indifference," to quote Kabir, an Indian poet of the 15th century who became a Saint.

No murder for Kabir, no syphilis, phthisis, cynic alcoholism or dementia. Just Sanctity.

A proper ending for a Poet at last.

New York, 7 December 2018

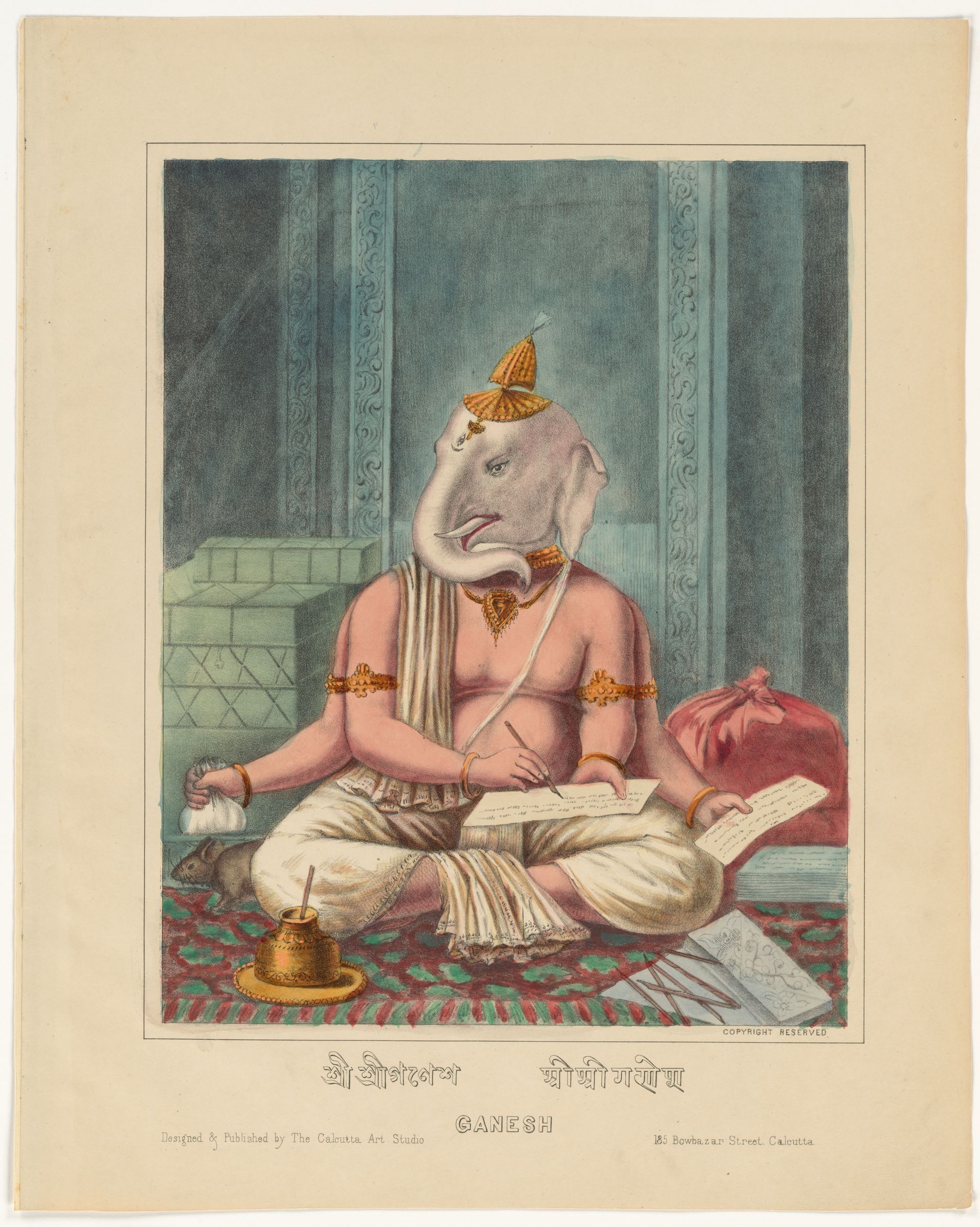

Murielle Mobengo is a Poet and a lover of classical literature. She inquires poetic existence, the origins of Poetry, and its proximity with Mythology, the religious sources of Art, and Philosophy. Murielle composes in English, French, German, and has a fondness for Western ancient languages & Sanskrit. She founded Revue {R}évolution in 2019, in New York, to share her passion for European literature, poetry, Eastern philosophy, meaningful art, and mythology. Passionate about symbols–which in her opinion and as a whole, express pantheism–, she defines herself as a symbolist and a mythologist. Murielle Mobengo is a disciple of Kashmiri Shaivism, the non-dualist Eastern philosophy where Yoga originated.

Comment this article!

One rule: Be courteous and relevant. Thank you!

Revue {R}évolution