POÎÉSIS | A Journey from The Mundane to The Divine

POIESIS (AMOR FATI)

The Structure of Poetry: Of Substance & Style

New Title

Poetry is often viewed as a mysterious art form due to the singularity of its language. Rich traditions of poets from the East to the West have expressed this evocative and ancient lingua with erudition, grace, and elegance for humanity's delight, but also to educate future generations of poets.

In light of the significant amount of poems Revue {R}évolution rejects, it becomes imperative to delve into the heart of poetry itself.

This article aims to offer insight into the intrinsic structure of poetry, the evolution of language, and what we may have relinquished in the process.

Below is a lighter version of this article in video.

We encourage you to read the article in its entirety.

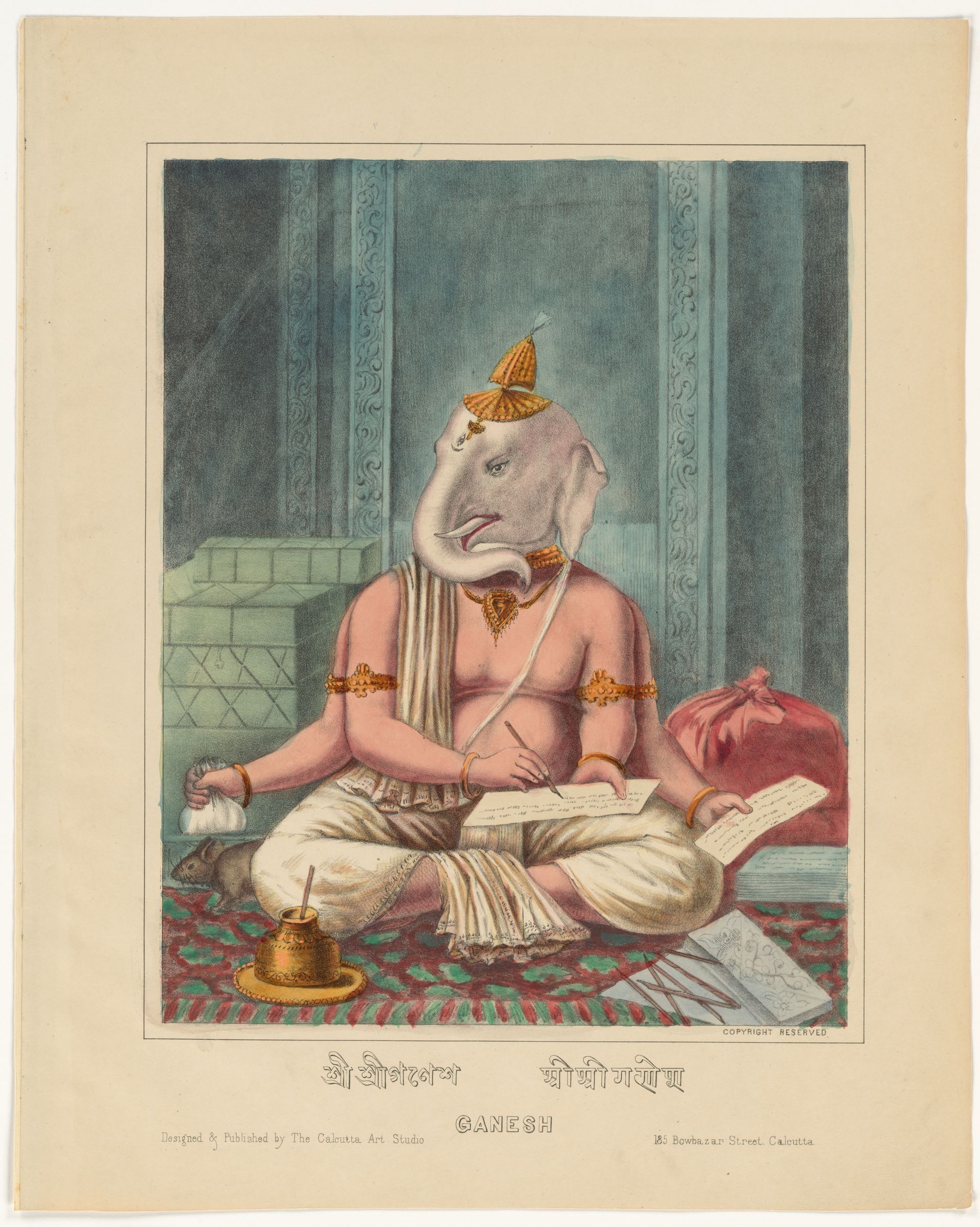

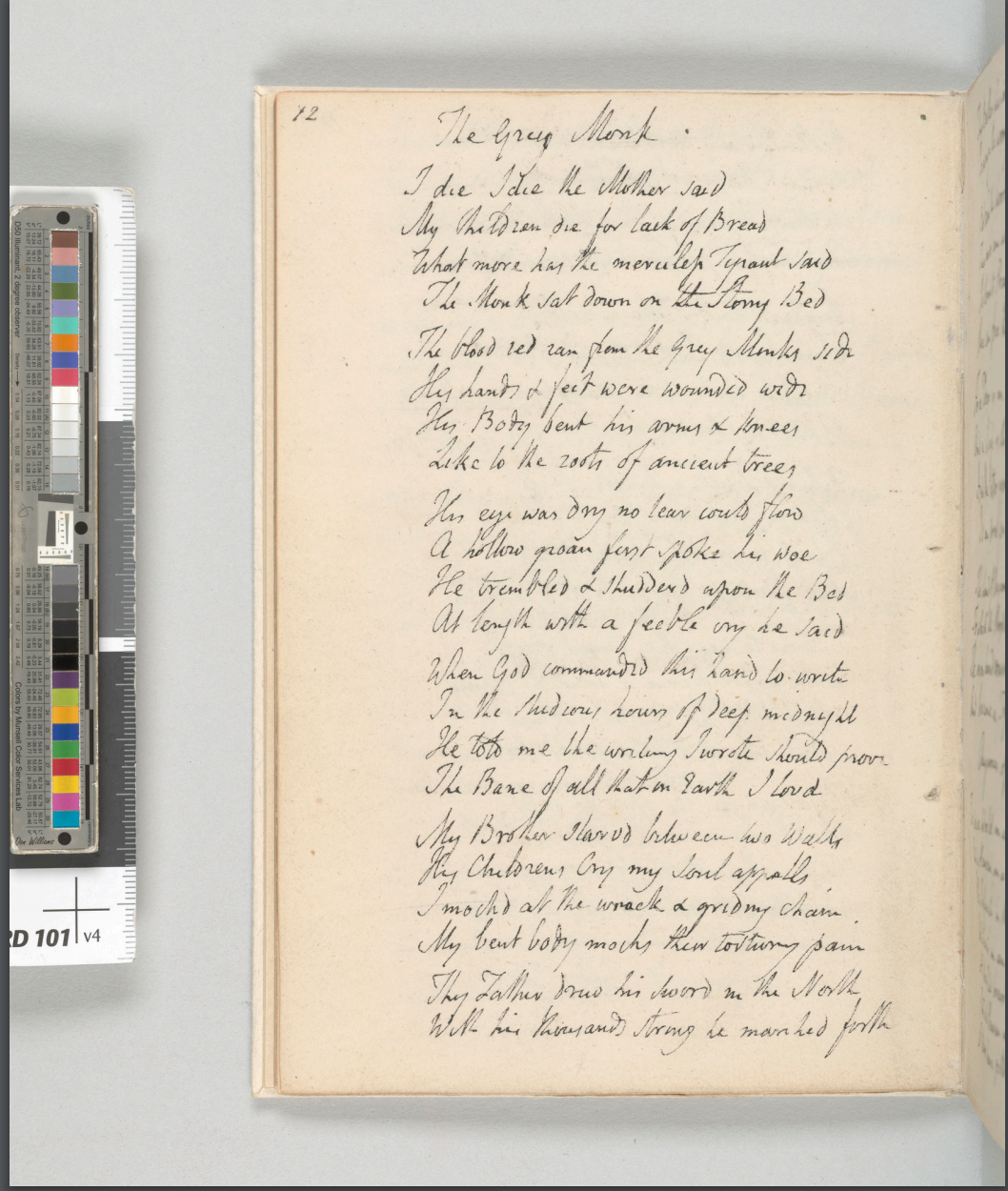

A page from William Blake's Pickering Manuscript.

Source:

The Morgan Library & Museum

The substance of poetry

Today, the term "poetry" is a nebulous concept, with each person having their own interpretation. However, beneath this subjective veil lies a significant truth: words hold meaning. Consider the concept of time; philosophers have penned numerous pages on its nature, but when you need to be punctual for a meeting, reading a philosophical treatise like Heidegger's Being and Time won't help. Clocks, tangible and practical, teach us the essence of punctuality. Our bodies also teach us what time is, as they age and die. Just as time is a science with its techniques, poetry, too, requires tools and «un savoir-faire», a know-how or technique.

Roots of meter

To understand the essence of poetry, we must turn to its origins. The earliest poetic expressions in human literature were intertwined with religion. Religion, at its core, is about belief, the sacred or divine dimension of/beyond existence where the archetype of "God" represents the absolute and the transcendent. Thus, poets and mystics have consistently used poetry to explore the unfathomable, from the invisible deity to the mortal body, the nature of life and death, and the human experience itself.

Notable examples of such poetic works include Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, but also canons of contemporary religions like The Vedas, The Mahabharata by Vyasa, The Quran, The Bible, The Gathas (Zoroastrianism scriptures, said to have been written by Persian poet and prophet Zarathustra). These enduring works have transcended time and shaped nations, societies, and cultures.

Ancient European poets (Greek, Roman, and late German) served as the primary source of inspiration for the masterpieces of classical literature. Even texts like the Norse Eddas are experiencing a revival, influencing contemporary religious practices with Asatrù and social structures. Not to mention the Hollywood film industry, with its same-old-same-old usage of shallow mythical interpretation which has exploited these texts, ad nauseam.

So, poets who penned these timeless works of literature surely deserve minute study and respect. One notable aspect worth mentioning is their adept utilization of highly stylized forms.

The marriage of subtance and style

This brings us to a profound question: does the subject of your poem dictate its form? Does grappling with deep philosophical questions make it easier to craft poetry in stylized forms that endure and influence generations? The answer lies within, ready to be discovered through active reflection and practice.

How language evolved from poetry to prose

As humanity gained mastery over its environment, language also evolved. The first non-rhyming texts and movements challenging rhymes in European literature appeared in the mid 19th century, as romanticism battled to survive the question of “l’art pour l’art” and a utilitarian frenzy inherited from the Age of Enlightenment.

In France, for instance, Aloysius Bertrand championed prose as a privileged mode of poetic expression, when he published Gaspard de la nuit, a piece revealing an aptitude for storytelling probably hiding a certain deficiency in versification talent. Eminent poets and versifiers followed suit, forsaking rhyme and meter in pursuit of the freedoms of prose. Some did so with philosophical depth and narrative brilliance, exemplified by Baudelaire's "Petits poèmes en prose," which retained profound symbolism. Others, like the young Rimbaud in Une saison en enfer, displayed dazzling poetic accents and sutra-like insights.

The prose frenzy reached its zenith during the Dada and Surrealist movements, permeating the realm of visual art. Dada, a one-man movement, was short-lived. Surrealism persisted, spread beyond Europe, boasting talented writers, thinkers, and poets, but died of extravaganza, lack of vision, and overall immaturity. With both these movements now consigned to the annals of history, we find ourselves confronted with the enigmatic realm of "prose poetry." However, current "prose poetry" pales in comparison to the linguistic craftsmanship Surrealists and early champions of prose in poetry exhibited.

It also falls short of the initiatory storytelling brilliance seen in the poetic works of William Blake, Herman Hesse or later, Miguel Angel Asturias, to name only a few poets who have excelled at harnessing the poetic dimension of life through prose, and surpassed the intellectual prowess of André Breton and the spontaneous genius of Apollinaire.

Now, from a historical perspective, in the aftermath of the industrial revolution and the heavy mechanization of human societies that ensued in the West, language became more analytical and descriptive, rooted in immediate sensory perception. Poetry, once deeply existential, lyrical, and mystical, underwent a rapid prosaic transformation. Poets began to explore everyday subjects such as love, hate, family, politics, and more as if they were transcendental (they are not; they all end with death). This shift in focus led to a change in the expressive structure of poetry.

The rhythmic cadence which once defined poetry waned, and verses, with their cosmic, universal resonance, began to disappear. Poetry transformed into prose, while prose failed even more at retaining poetic qualities. Poets explored “free verse,” a paradoxical concept which pretends to defy the constraints of traditional verse. Remember the definition of verse as inherently structured with metrical rhythms. Realize verses cannot be free.

Preserving tradition, preserving language

Poetry is a time-honored tradition, and our publication proudly showcases poets who adhere to this noble genre. In our fifth issue, readers will discover valuable recommendations for poetry books, especially for those who find the process of composing verses to be challenging – which, indeed, it can be.

This challenge emerges not only from poetry's departure from its elevated, ethereal domain since the 19th century, but also from the type of poetry extensively promoted in the media today, which has lost its stylized form and philosophical substance. Fortunately, many poets from the far and near past achieved mastery, elevating their work to timelessness. Because of their enduring relevance to the core questions of human existence, their work cannot be cancelled, no matter how hard some may try.

Murielle Mobengo is Editor-in-chief, founder of Revue {R}évolution and author of The Poetical Manifesto: How fame kills creativity. She inquires poetic existence, the origins of poetry, and its proximity with art, mythology, and philosophy. Murielle is a poet, a teller of initiatic tales, and a translator. She composes in English, French, and German, and has a fondness for Western ancient languages & Sanskrit. Murielle authored a ten-year poetry collection in French and is working on a multilingual poetry and mythology collection, among other projects she hopes to finish before she turns 80. She founded a unique counseling practice in cultural leadership development for poets and artists.

Comment this article!

One rule: Be courteous and relevant. Thank you!

Revue {R}évolution